Indonesia holds 40% of the world’s geothermal reserves—but why is it still underperforming? This comparative analysis unpacks how Kenya, Türkiye, and the U.S. are leveraging public-private partnerships (PPPs) to de-risk geothermal development, and what critical lessons Indonesia must learn to unlock its clean energy future.

Introduction

Public-private Partnerships (PPPs) are key drivers for infrastructure development, blending public oversight with private sector efficiency. In sectors like geothermal energy—where upfront risks are high—PPPs offer a mechanism to distribute financial burdens while accelerating growth.

Indonesia, despite holding ~40% of global geothermal reserves, lags behind. A comparative study by Sri Sutama et al. explores global best practices from Kenya, Türkiye, and the United States, providing valuable insights to guide Indonesia’s geothermal development journey.

Understanding PPPs in the Energy Sector

A Public-private Partnership (PPP) is a collaborative agreement where the government and private companies work together to deliver public services such as roads, hospitals, and energy infrastructure. In a PPP, both risks and rewards are shared between public and private entities.

Key Features of PPPs:

- Leveraging private sector expertise and experience

- Fostering competition and innovation

- Sharing risks

- Restructuring public service delivery

- Minimizing lifecycle costs through project bundling

- Achieving economies of scale

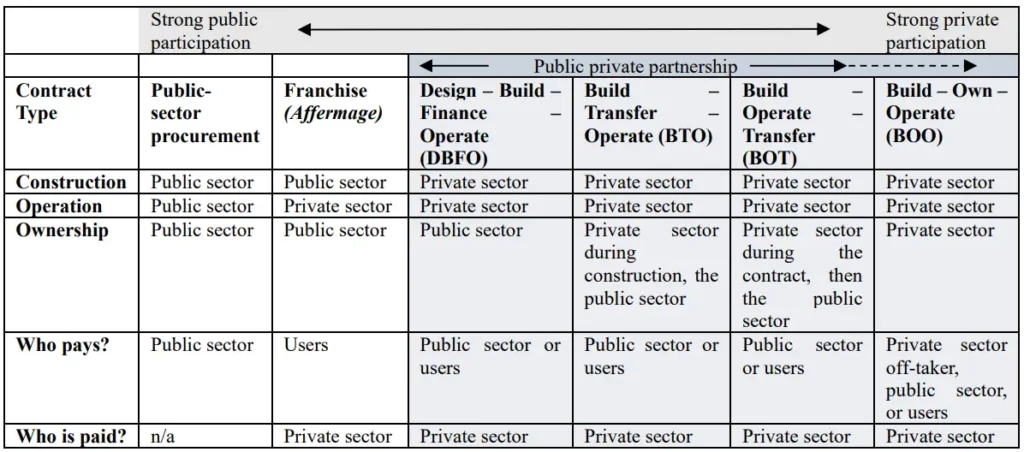

Different Models of Public-private Provision of Infrastructure

The table below provides a comparative overview of various PPP contract types, ranging from strong public participation models to those with dominant private sector involvement, highlighting key distinctions in construction, operation, ownership, funding responsibilities, and revenue flows.

Global Use of PPPs in Infrastructure Development

In developing countries, PPPs have primarily been employed to bridge infrastructure gaps, notably in the transport and energy sectors. From 1999 to 2021:

- 56% of private sector investments in developing countries were structured as PPPs.

- If Build-Own-Operate (BOO) arrangements are included, the figure is even higher.

- Approximately 90% of these investments were concentrated in transport and energy sectors, with 36% specifically in energy—largely in electricity generation.

Conversely, in developed countries, PPPs are more commonly applied to sectors like education, health services, waste management, and public buildings.

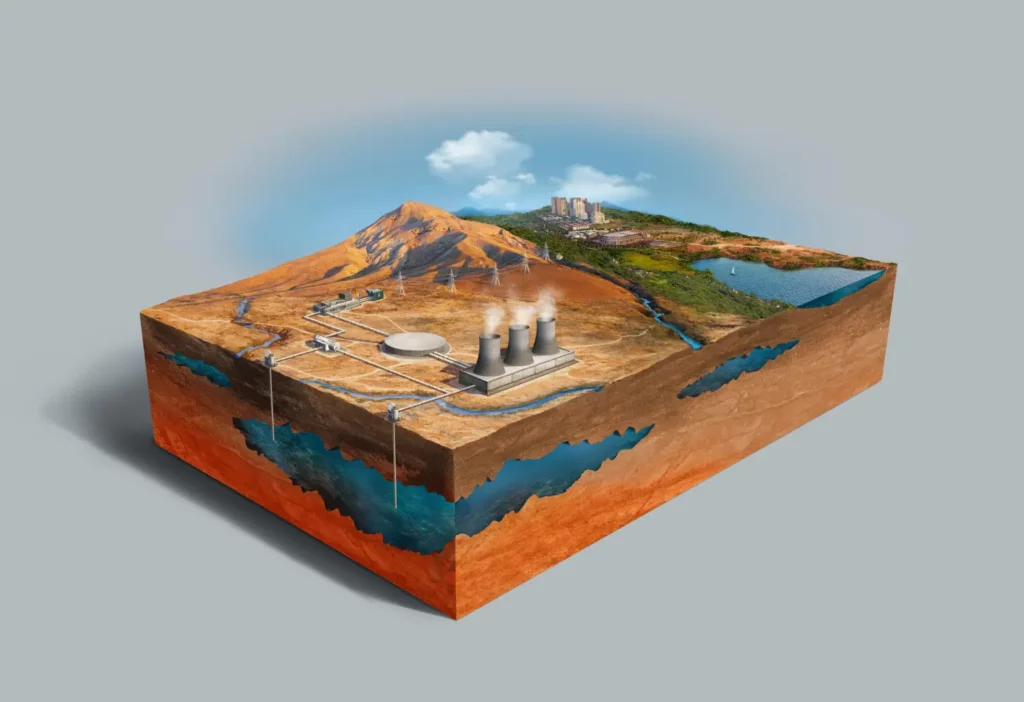

PPPs in Geothermal Energy

Despite its enormous potential, geothermal energy adoption has significantly lagged behind solar and wind energy. One of the main challenges lies in the high level of unpredictability during the early stages of geothermal projects. The risks are substantial in the exploration phase, making private investors hesitant to engage without significant public sector support.

In geothermal PPPs:

- Early-stage investments carry the highest risks due to the uncertainty of viable resource findings.

- These phases typically rely on public sector investment.

- Private investors usually enter at later, more secure stages of project development.

Comparative Case Studies: Geothermal PPPs

A comparative analysis of geothermal development frameworks across Kenya, Türkiye, the United States, and Indonesia is outlined below to highlight key structural, regulatory, and market differences influencing project outcomes.

| Aspect | Kenya | Türkiye | United States | Indonesia |

| Installed Capacity | 985 MW (2024) | 1,734 GW (2024) | 3,937 MW (2024) | 2,653 GW (2024) |

| Market Structure | Liberalized, single buyer with open Independent Power Producer (IPP) access | Liberalized generation, state-controlled grid | Mixed: deregulated and regulated by state | Single-buyer (PLN) |

| Public Sector Role | Geothermal Development Company (GDC) funds exploration | Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration (MTA) initial role, now private-led | Incentives + grants (federal & state) | Gov. drilling, limited PPPs |

| Private Sector Role | Post-exploration entry | Private-led via feed-in tariffs | Dominant, competitive | IPPs under PLN contracts |

| Risk Tools | GDC, public funds | Risk Sharing Mechanism (RSM), feed-in tariffs | Tax credits, grants | Geothermal Resource Risk Mitigation (unused), gov. drilling |

| PPP Usage | Build-Own-Operate-Transfer (BOOT), Build-Own-Operate (BOO), Build-Own-Transfer (BOT) widely used | Limited PPPs, some BOO | No formal PPPs, private financing + aid | Institutional PPPs, no geothermal focus |

| Key Incentives | Loans, guarantees | Feed-in Tariff (FiT), local content bonuses | Tax credits, depreciation, Research & Development (R&D) funding | Benchmark tariffs, viability gap fund |

| Challenges | Public fund reliance | Currency risks, reduced public role | Regulatory barriers, slow pace | Early-stage risk, limited private entry |

| Electricity Pricing | Cost-reflective | Fixed FiT in USD (pre-2021), revised in 2023 | Competitive pricing | Benchmark pricing |

| Future Goals | 5 GW by 2030 | Stabilize post-policy shifts | 13–60 GW target | 7.2 GW by 2030 |

Key Insights on Comparative Case Studies

🇰🇪 Kenya

- Public-led de-risking (GDC) is critical.

- PPP structures like BOO/BOOT attract private sector post-exploration.

🇹🇷 Türkiye

- Feed-in tariffs and local incentives boosted growth.

- Currency volatility has challenged long-term private involvement.

🇺🇸 United States

- Strong private sector leadership, enabled by comprehensive government support.

- Tax incentives and state grants reduce early-stage burdens.

Opportunities and Recommendations for Indonesia

To unlock its geothermal potential, Indonesia must refine its approach based on international best practices:

1. Strengthen Public-Led Risk Mitigation

- Create a dedicated public entity (similar to Kenya’s GDC) for early-stage exploration.

- Enhance the utilization of schemes like GREM by making them more accessible and attractive to private investors.

- Learn from the U.S. model, where grants help share early-stage development risks.

2. Provide Comprehensive Incentives

- Take inspiration from Türkiye’s feed-in tariff programs that stimulated private investment.

- Emulate U.S. incentives, including grants during exploration, tax credits, accelerated depreciation, and R&D funding.

- Implement comprehensive support structures to attract sustained private sector engagement throughout the project lifecycle.

3. Formalize Geothermal within the PPP Framework

- Explicitly integrate geothermal into Indonesia’s national PPP strategy.

- Enable geothermal projects to access viability gap funds (VGF) and project preparation support, just like other infrastructure sectors.

4. Gradually Deregulate the Electricity Market

- International cases suggest that electricity market liberalization supports geothermal growth.

- Allow geothermal operators to sell electricity through Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) and wholesale markets.

- Introduce market-based pricing to enhance the viability of geothermal investments, encouraging innovation and cost efficiency.

Conclusion

Indonesia’s geothermal sector stands at a crucial crossroads. Learning from international experiences, particularly Kenya’s public de-risking, Türkiye’s tariff incentives, and the United States’ comprehensive support frameworks, can provide Indonesia with a strategic roadmap.

By enhancing early-stage risk mitigation, offering comprehensive incentives, establishing clear PPP frameworks, and gradually liberalizing the market, Indonesia can unlock its vast geothermal potential—powering a more sustainable and prosperous energy future.

At Energy Academy Indonesia (ECADIN), our mission is to support the global energy transition by accelerating the development of renewable energy, particularly geothermal, and promoting just sustainable growth. We’re proud to contribute research, innovation, advocacy, and to connect expertise, knowledge, business actors, and financing means. We value our diversity and focus on creating an inclusive environment where our team and partners can flourish.

References:

- Comparative Analysis of Geothermal PPPs: International Insights and Indonesia’s Cases

- Public-private Partnerships: Principles of Policy and Finance

Summarized by Moh. Rifli Mubarak (Climate & Sustainability Officer at ECADIN) from Paper titled “Comparative Analysis of Geothermal PPPs: International Insights and Indonesia’s Cases” by Candra Sri Sutama et al.